Lincoln Memorial Site Plan Drawing

| Lincoln Memorial | |

| U.S. National Register of Historic Places | |

| U.S. National Memorial | |

Aerial view of the Lincoln Memorial, 2010 | |

| Prove map of Primal Washington, D.C. Show map of the District of Columbia | |

| Location | Due west Finish of National Mall, Washington, D.C. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°53′21.iv″N 77°3′0.v″West / 38.889278°N 77.050139°W / 38.889278; -77.050139 Coordinates: 38°53′21.4″N 77°3′0.five″Westward / 38.889278°N 77.050139°W / 38.889278; -77.050139 |

| Area | 27,336 square feet (2,539.6 1000two) |

| Congenital | 1914–1922 |

| Architect | Henry Salary (architect) Daniel Chester French (sculptor) |

| Architectural manner | Greek Revival[1] |

| Visitation | 7,808,182 (2019)[two] |

| Website | Lincoln Memorial |

| NRHP referenceNo. | 66000030[ane] |

| Added to NRHP | October fifteen, 1966 |

Time to come site of the Memorial, c.1912

The Lincoln Memorial is a U.s.a. national memorial congenital to honor the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. It is on the western end of the National Mall in Washington, D.C., beyond from the Washington Monument, and is in the grade of a neoclassical temple. The memorial's architect was Henry Bacon. The designer of the memorial interior'south large central statue, Abraham Lincoln (1920), was Daniel Chester French; the Lincoln statue was carved past the Piccirilli brothers.[3] The painter of the interior murals was Jules Guerin, and the epitaph above the statue was written by Royal Cortissoz. Defended in May 1922, it is one of several memorials built to award an American president. It has always been a major tourist attraction and since the 1930s has sometimes been a symbolic center focused on race relations.

The building is in the form of a Greek Doric temple and contains a large seated sculpture of Abraham Lincoln and inscriptions of two well-known speeches by Lincoln, the Gettysburg Accost and his 2nd inaugural accost. The memorial has been the site of many famous speeches, including Martin Luther Rex Jr.'due south "I Accept a Dream" spoken communication delivered on August 28, 1963, during the rally at the end of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Like other monuments on the National Mall – including the nearby Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Korean War Veterans Memorial, and World War II Memorial – the national memorial is administered by the National Park Service nether its National Mall and Memorial Parks grouping. Information technology has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places since October xv, 1966, and was ranked seventh on the American Institute of Architects' 2007 list of America's Favorite Architecture. The memorial is open up to the public 24 hours a day, and more than seven meg people visit it annually.[iv]

History [edit]

The commencement public memorial to Us President Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C., was a statue by Lot Flannery erected in front of the Commune of Columbia Urban center Hall in 1868, 3 years after Lincoln'south bump-off.[five] [6] Demands for a plumbing fixtures national memorial had been voiced since the time of Lincoln's decease. In 1867, Congress passed the start of many bills incorporating a commission to cock a monument for the sixteenth president. An American sculptor, Clark Mills, was chosen to design the monument. His plans reflected the nationalistic spirit of the time, and called for a 70-pes (21 yard) structure adorned with six equestrian and 31 pedestrian statues of colossal proportions, crowned by a 12-foot (three.7 chiliad) statue of Abraham Lincoln. Subscriptions for the project were insufficient.[seven]

The thing lay dormant until the start of the 20th century, when, under the leadership of Senator Shelby M. Cullom of Illinois, 6 separate bills were introduced in Congress for the incorporation of a new memorial committee. The first five bills, proposed in the years 1901, 1902, and 1908, met with defeat considering of opposition from Speaker Joe Cannon. The sixth bill (Senate Beak 9449), introduced on December 13, 1910, passed. The Lincoln Memorial Commission had its first meeting the following year and United States President William H. Taft was chosen as the committee's president. Progress continued at a steady step and by 1913 Congress had approved of the commission's pick of design and location.[vii]

At that place were questions regarding the committee's plan. Many thought that architect Henry Bacon'due south Greek temple design was far as well ostentatious for a man of Lincoln's apprehensive character. Instead, they proposed a simple log cabin shrine. The site as well did not go unopposed. The recently reclaimed land in West Potomac Park was seen past many to be either too swampy or too inaccessible. Other sites, such as Union Station, were put forth. The Commission stood firm in its recommendation, feeling that the Potomac Park location, situated on the Washington Monument–Capitol axis, overlooking the Potomac River and surrounded by open state, was platonic. Furthermore, the Potomac Park site had already been designated in the McMillan Plan of 1901 to be the location of a hereafter monument comparable to that of the Washington Monument.[7] [8]

With Congressional approval and a $300,000 allocation, the project got underway. On February 12, 1914, contractor M. F. Comer of Toledo, Ohio; resident member of the memorial's committee, former Senator Joseph C. Due south. Blackburn of Kentucky; and the memorial'southward designer, Henry Bacon conducted a groundbreaking ceremony by turning over a few spadefuls of world.[9] The post-obit month is when actual construction began. Work progressed steadily according to schedule. Some changes were made to the program. The statue of Lincoln, originally designed to be x feet (3.0 1000) alpine, was enlarged to 19 feet (five.8 g) to preclude information technology from being overwhelmed by the huge chamber. As late as 1920, the decision was made to substitute an open portal for the bronze and glass grille which was to take guarded the entrance. Despite these changes, the Memorial was finished on schedule. Committee president William H. Taft – who was and so Chief Justice of the U.s. – dedicated the Memorial on May 30, 1922, and presented it to Usa President Warren One thousand. Harding, who accepted it on behalf of the American people. Lincoln'due south only surviving son, 78-year-old Robert Todd Lincoln, was in attendance.[10] Prominent African Americans were invited to the upshot and discovered upon arrival they were assigned a segregated section guarded by U.Due south. Marines.[eleven]

The Memorial was listed on the National Annals of Historic Places on Oct 15, 1966.[12]

Exterior [edit]

The outside of the Memorial echoes a classic Greek temple and features Yule marble quarried from Colorado. The structure measures 189.7 by 118.5 feet (57.8 by 36.1 thousand) and is 99 feet (30 1000) tall. Information technology is surrounded past a peristyle of 36 fluted Doric columns, one for each of the 36 states in the Union at the time of Lincoln's death, and 2 columns in-antis at the archway behind the pillar. The columns stand 44 feet (13 m) tall with a base diameter of 7.5 feet (2.3 1000). Each cavalcade is built from 12 drums including the uppercase. The columns, like the exterior walls and facades, are inclined slightly toward the building'south interior. This is to recoup for perspective distortions which would otherwise brand the memorial appear to burl out at the peak when compared with the bottom, a common feature of Aboriginal Greek architecture.[xiii]

Above the pillar, inscribed on the frieze, are the names of the 36 states in the Union at the fourth dimension of Lincoln's expiry and the dates in which they entered the Union.[Note i] Their names are separated by double wreath medallions in bas-relief. The cornice is composed of a carved roll regularly interspersed with projecting lions' heads and ornamented with palmetto cresting along the upper border. To a higher place this on the attic frieze are inscribed the names of the 48 states nowadays at the time of the Memorial'due south dedication. A bit higher is a garland joined by ribbons and palm leaves, supported by the wings of eagles. All ornamentation on the friezes and cornices was washed by Ernest C. Bairstow.[13]

The Memorial is anchored in a concrete foundation, 44 to 66 feet (13 to 20 m) in depth, synthetic past Yard. F. Comer and Company and the National Foundation and Engineering science Company, and is encompassed by a 187-by-257-foot (57 past 78 m) rectangular granite retaining wall measuring 14 anxiety (iv.3 k) in height.[13]

Leading up to the shrine on the east side are the principal steps. Beginning at the edge of the Reflecting Pool, the steps rise to the Lincoln Memorial Circle roadway surrounding the building, and so to the primary portal, intermittently spaced with a series of platforms. Flanking the steps every bit they approach the entrance are ii buttresses each crowned with an 11-human foot (3.iv m) tall tripod carved from pink Tennessee marble[13] by the Piccirilli Brothers.[14]

Interior [edit]

The Memorial'south interior is divided into three chambers by two rows of four Ionic columns, each 50 feet (15 m) tall and 5.five feet (1.7 m) beyond at their base. The central chamber, housing the statue of Lincoln, is 60 anxiety wide, 74 feet deep, and lx feet high.[fifteen] The north and due south chambers brandish carved inscriptions of Lincoln's 2d countdown address and his Gettysburg Accost.[Note 2] Adjoining these inscriptions are pilasters ornamented with fasces, eagles, and wreaths. The inscriptions and adjoining ornamentation are past Evelyn Beatrice Longman.[13]

The Memorial is replete with symbolic elements. The 36 columns correspond united states of america of the Union at the fourth dimension of Lincoln'south decease; the 48 stone festoons in a higher place the columns correspond the 48 states in 1922. Inside, each inscription is surmounted by a 60-by-12-human foot (18.iii by 3.seven m) landscape by Jules Guerin portraying principles seen as evident in Lincoln's life: Liberty, Liberty, Morality, Justice, and the Law on the southward wall; Unity, Fraternity, and Charity on the north. Cypress trees, representing Eternity, are in the murals' backgrounds. The murals' pigment incorporated kerosene and wax to protect the exposed artwork from fluctuations in temperature and moisture.[xvi]

The ceiling consists of bronze girders ornamented with laurel and oak leaves. Between these are panels of Alabama marble, saturated with paraffin to increase translucency. Simply feeling that the statue required even more light, Bacon and French designed metal slats for the ceiling to muffle floodlights, which could be modulated to supplement the natural low-cal; this modification was installed in 1929. The one major alteration since was the addition of an elevator for the disabled in the 1970s.[16]

Undercroft [edit]

Below the memorial is an undercroft. Due to h2o seeping through the calcium carbonate within the marble, over fourth dimension stalactites and stalagmites have formed inside information technology.[17] During structure, graffiti was scrawled on it past workers,[xviii] [19] and is considered historical by the National Park Service.[18] During the 1970s and 1980s, at that place were regular tours of the undercroft.[20] The tours stopped abruptly in 1989 after a company noticed asbestos and notified the Service.[21] For the memorial's centennial in 2022, the undercroft is planned to be open to visitors post-obit a rehabilitation project funded by David Rubenstein.[22] [23]

Statue [edit]

| IN THIS TEMPLE |

| —Epitaph by Royal Cortissoz |

Lying between the due north and south chambers of the open-air Memorial is the central hall, which contains the big solitary effigy of Abraham Lincoln sitting in contemplation. Its sculptor, Daniel Chester French, supervised the half-dozen Piccirilli brothers (Ferruccio, Attilio, Furio, Masaniello, Orazio, and Getulio) in its construction, and information technology took four years to consummate.

The 175-short-ton (159 t) statue, carved from Georgia white marble, was shipped in 28 pieces.[16] Originally intended to exist simply ten anxiety (three.0 m) tall, the sculpture was enlarged to nineteen feet (5.8 m) from caput to foot considering it would look small-scale within the extensive interior infinite.[24] If Lincoln were depicted standing, he would be 28 feet (eight.5 m) tall.

The widest bridge of the statue corresponds to its height, and it rests upon an oblong pedestal of Tennessee marble 10 anxiety (3.0 m) high, xvi feet (4.nine m) broad, and 17 anxiety (5.2 m) deep. Directly beneath this lies a platform of Tennessee marble about 34.5 anxiety (ten.5 chiliad) long, 28 feet (8.5 m) broad, and vi.5 inches (0.17 m) high. Lincoln'due south arms rest on representations of Roman fasces, a subtle touch that associates the statue with the Augustan (and imperial) theme (obelisk and funerary monuments) of the Washington Mall.[25] The statue is discretely bordered by ii pilasters, one on each side. Between these pilasters, and above Lincoln's head, is engraved an epitaph of Lincoln[16] by Royal Cortissoz.[26]

Sculptural features [edit]

The sculptor's possible use of sign language is speculated, as the statue's left mitt forms an "A" while the right hand portrays an "L"

An urban legend holds that the face of General Robert East. Lee is carved onto the dorsum of Lincoln's caput,[27] and looks back across the Potomac toward his onetime habitation, Arlington House (now inside the bounds of Arlington National Cemetery). Another popular fable is that Lincoln'south hands are shown using sign language to represent his initials, his left manus signing an A and his right signing an 50. The National Park Service denies both legends.[27]

However, historian Gerald Prokopowicz writes that, while it is not clear that sculptor Daniel Chester French intended Lincoln's easily to exist formed into sign language versions of his initials, it is possible that French did intend it, considering he was familiar with American Sign Language, and he would have had a reason to practice then, that is, to pay tribute to Lincoln for having signed the federal legislation giving Gallaudet University, a academy for the deaf, the authority to grant college degrees.[28] The National Geographic Society'south publication "Pinpointing the By in Washington, D.C." states that Daniel Chester French had a son who was deaf and that the sculptor was familiar with sign language.[29] [30] Historian James A. Percoco has observed that, although there are no extant documents showing that French had Lincoln's hands carved to correspond the letters "A" and "L" in American Sign Language, "I think you tin can conclude that it's reasonable to accept that kind of summation near the easily."[31]

Sacred space [edit]

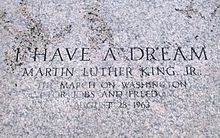

The location on the steps where King delivered the speech is commemorated with this inscription.

The Memorial has become a symbolically sacred venue, particularly for the Civil Rights Move. In 1939, the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to permit the African-American contralto Marian Anderson to perform earlier an integrated audience at the organization's Constitution Hall. At the proposition of Eleanor Roosevelt, the wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harold L. Ickes, the Secretary of the Interior, bundled for a performance on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sun of that year, to a live audience of 75,000 and a nationwide radio audience.[32] On June 29, 1947, Harry Truman became the starting time president to address the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The speech took place at the Lincoln Memorial during the NAACP convention and was carried nationally on radio. In that voice communication, Truman laid out the need to end discrimination, which would be advanced past the first comprehensive, presidentially proposed civil rights legislation.[33]

On August 28, 1963, the memorial grounds were the site of the March on Washington for Jobs and Liberty, which proved to be a high point of the American Civil Rights Motility. It is estimated that approximately 250,000 people came to the outcome, where they heard Martin Luther King Jr., evangelize his celebrated "I Have a Dream" speech communication before the memorial honoring the president who had issued the Emancipation Announcement 100 years earlier. Male monarch'south speech, with its language of patriotism and its evocation of Lincoln's Gettysburg Address, was meant to friction match the symbolism of the Lincoln Memorial every bit a monument to national unity.[34] Labor leader Walter Reuther, an organizer of the march, persuaded the other organizers to move the march to the Lincoln Memorial from the Capitol Building. Reuther believed the location would exist less threatening to Congress and that the occasion would be particularly appropriate underneath the gaze of Abraham Lincoln's statute.[35] The D.C. police also appreciated the location because it was surrounded on three sides past water, and then that whatever incident could be easily contained.[36]

20 years later, on August 28, 1983, crowds gathered again to marking the 20th Anniversary Mobilization for Jobs, Peace and Liberty, to reverberate on progress in gaining civil rights for African Americans and to commit to correcting standing injustices. King's oral communication is such a office of the Lincoln Memorial story, that the spot on which King stood, on the landing eighteen steps below Lincoln'due south statue, was engraved in 2003 in recognition of the 40th ceremony of the event.[37]

At the memorial on May 9, 1970, President Richard Nixon had a centre-of-the-night impromptu, brief meeting with protesters who, but days after the Kent State shootings, were preparing to march against the Vietnam War.[38]

Vandalism [edit]

In September 1962, among the civil rights movement, vandals painted the words "nigger lover" in ane-pes-high (30 cm) pink letters on the rear wall.[39]

On July 26, 2013, the statue's base and legs were splashed with green paint.[40] A 58-year-sometime Chinese national was arrested and admitted to a psychiatric facility; she was later on establish to be incompetent to stand trial.[41]

On February 27, 2017, graffiti written in permanent marker was found at the memorial, the Washington Monument, the District of Columbia State of war Memorial, and the National Globe War Ii Memorial, maxim "Jackie shot JFK", "blood examination is a lie", likewise equally other claims. Street signs and utility boxes were likewise defaced. Authorities believed that a single person was responsible for all the vandalism.[42]

On August xv, 2017, Reuters reported that "Fuck constabulary" was spray painted in red on 1 of the columns. The initials "1000+E" were etched on the aforementioned pillar. A "mild, gel-type architectural pigment stripper" was used to remove the pigment without damaging the memorial. All the same, the etching was deemed "permanent damage." A Smithsonian Institution directional sign several blocks abroad was also defaced.[43] [44]

On September 18, 2017, Nurtilek Bakirov from Kyrgyz republic was arrested when a police force officeholder saw him vandalizing the Memorial at effectually 1:00 PM EDT. Bakirov used a penny to carve the letters "HYPT MAEK" in what appeared to exist Cyrillic letters into the fifth colonnade on the n side. Equally of September 20, 2017[update], law do not know what the words hateful, although there is a possibility that they incorporate a reference to the vandal'south name. Court documents indicate that the letters cannot be completely removed, only could be polished at the cost of approximately $2,000. A conservator for the National Park Service said that the stone would weather over time, helping to obscure the letters, although she characterized it as "permanent damage".[45]

On May 30, 2020, during nationwide protests in the wake of the murder of George Floyd, vandals spray-painted "Yall not tired yet?" beside the steps leading to the memorial. The National World War II Memorial was too vandalized that night.[46] [47]

In popular civilization [edit]

With Reflecting Pool

At sunrise

Daytime

At sunset

As one of the most prominent American monuments, the Lincoln Memorial is often featured in books, films, and television receiver shows that take place in Washington; by 2003 information technology had appeared in over threescore films,[48] and in 2009, Marking S. Reinhart compiled some brusk sketches of dozens of uses of the Memorial in film and idiot box.[49]

Some examples of films include Frank Capra'due south 1939 motion-picture show Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, where in a key scene the statue and the Memorial's inscription provide inspiration to freshman Senator Jefferson Smith, played by James Stewart.[50] The Park Service did not want Capra to moving-picture show at the Memorial, so he sent a big crew elsewhere as a lark while a smaller crew filmed Stewart and Jean Arthur within the Memorial.[51]

Many of the appearances of the Lincoln Memorial are actually digital visual effects, due to restrictive filming rules.[52] As of 2017, according to the National Park Service, "Filming/photography is prohibited higher up the white marble steps and the interior chamber of the Lincoln Memorial."[53]

Mitchell Newton-Matza said in 2016 that "Reflecting its cherished identify in the hearts of Americans, the Lincoln Memorial has often been featured prominently in popular culture, especially motion pictures."[54] According to Tracey Gilded Bennett, "The majesty of the Lincoln Memorial is a big draw for motion picture location scouts, producers, and directors because this landmark has appeared in a considerable number of films."[55]

Jay Sacher writes:

From high to low, the memorial is cultural autograph for both American ethics and 1960s radicalism. From Forrest Gump's Zelig-like insertion into anti-state of war rallies on the steps of the memorial, to the villainous Decepticon robots discarding the Lincoln statue and claiming it equally a throne. ... The memorial's place in the culture is assured even as it is parodied.[52]

Depictions on U.S. currency [edit]

From 1959 (the 150th ceremony of Lincoln's birth) to 2008, the memorial, with statue visible through the columns, was depicted on the reverse of the United States one-cent coin, which since 1909 has depicted a bust of Lincoln on its front.[56]

The memorial has appeared on the back of the U.S. five-dollar nib since 1929.[57] The front of the bill bears Lincoln's portrait.

Meet also [edit]

References [edit]

Informational notes [edit]

- ^ The date for Ohio was incorrectly entered as 1802, as opposed to the correct yr, 1803.

- ^ In the line from the second inaugural, "With high hope for the time to come," the F in FUTURE was carved every bit an E. To obscure this error the spurious bottom line of the E is not painted in with black paint.

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b "National Register Information Organization". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Jan 23, 2007.

- ^ "Annual Visitation Highlights". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved x July 2020.

- ^ "Lincoln Memorial National Memorial; Washington, DC National Park Service

- ^ "Annual Park Recreation Visitation (1904 – Last Calendar Yr)" National Park Service

- ^ "Renovation and Expansion of the Historic DC Courthouse" (PDF). DC Court of Appeals. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2011. Retrieved v October 2011.

- ^ "Washington'due south Lincoln: The First Monument to the Martyred President". The Intowner. Archived from the original on 14 January 2017. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ a b c NRHP Nomination, p. 4

- ^ Thomas, Christopher A. (2002) The Lincoln Memorial and American Life Princeton, New Bailiwick of jersey: Princeton Academy Press. ISBN 069101194X

- ^ Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn83045462/1914-02-12/ed-1/?st=text&r=0.841,0.403,0.173,0.167,0. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ NRHP Nomination, p. 5

- ^ Yellin, Eric S. (2013-04-22). Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Colour Line in Woodrow Wilson'southward America. UNC Press Books. ISBN978-1-4696-0721-4.

- ^ NRHP Nomination, p. six

- ^ a b c d east NRHP Nomination, p. 2

- ^ Concklin, Edward F. (1927) The Lincoln Memorial, Washington. United states of america Government Printing Part

- ^ U. Due south. Function of Public Buildings and Public Parks. Lincoln Memorial Building Statistics

- ^ a b c d NRHP Nomination, p. iii

- ^ United Press (August 28, 1957) "Lincoln Memorial has some stalactites" Lodi News-Sentinel

- ^ a b Avery, Jim (July 19, 2017). "v World-Famous Landmarks That Have Totally Weirdo Secrets". Cracked . Retrieved June 30, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Rivera and Weinstein, Gloria and Janet (September 2, 2016). "Take a 'Historic Graffiti' Tour Nether the Lincoln Memorial". ABC News . Retrieved June 30, 2021.

- ^ Hodge, Paul (October 27, 1977) "What's Afoot Under Abe Lincoln's Anxiety?" The Washington Post

- ^ Twoomey, Steve (Apr 9, 1990) "Monuments Losing Battle with Erosion" The Washington Post

- ^ Staff (ndg) "Lincoln Center Rehabilitation" National Park Service website

- ^ Reid, Chip (November 23, 2016) "Lincoln Memorial to get long-awaited makeover, secret visitor'southward center" CBS News

- ^ Dupré, Judith (2007). Monuments: America's History in Art and Memory. New York: Random House. pp. 86–95. ISBN978-1-4000-6582-0.

- ^ Run into Buchner, Edmund (1976). "Solarium Augusti und Ara Pacis", Römische Mitteilungen 83: 319–375; (1988). Die Sonnenuhr des Augustus: Kaiser Augustus und dice verlorene Republik (Berlin); P. Zanker The Augustan Program of Cultural Renewal Archived 2012-05-30 at annal.today for a total discussion of the Augustan conservatory and its architectural features.

- ^ "Lincoln Memorial Pattern Individuals". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-xi-02 .

- ^ a b "Lincoln Memorial: Frequently Asked Questions" on the National Park Service website

- ^ Prokopowicz, Gerald J. (2008) Did Lincoln Own Slaves? And Other Frequently Asked Questions About Abraham Lincoln. Pantheon. ISBN 978-0-375-42541-7

- ^ Evelyn, Douglas Due east. and Dickson, Paul A. (1999) On this Spot: Pinpointing the Past in Washington, D.C. National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-7499-7

- ^ Library.gallaudet.edu Archived 2009-01-04 at the Wayback Automobile

- ^ Percoco, James A., voice communication given on April 17, 2008, in the Jefferson Room of the National Archives and Records Administration as part of the National Annal'southward "Noontime Programs" lecture series. Broadcast on the C-Bridge cable television network on Apr four and Apr 5, 2009. c-spanvideo.org

- ^ "Eleanor Roosevelt and Marian Anderson". FDR Presidential Library & Museum. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Drinking glass, Andrew (2018-06-29). "Truman addresses NAACP, June 29, 1947". Politico . Retrieved 2021-07-27 .

- ^ Fairclough, Adam (1997) "Civil Rights and the Lincoln Memorial: The Censored Speeches of Robert R. Moton (1922) and John Lewis (1963)" Journal of Negro History v.82 pp.408–416.

- ^ Maraniss, David (2015). Once in a Great Metropolis: A Detroit Story. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 236. ISBN978-1-4767-4838-2. OCLC 894936463.

- ^ Jennings, Peter and Brewster, Todd (1998) The Century: A Chronicle of the 20th Century. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780385483278

- ^ "Stand Where Martin Luther King, Jr. Gave the "I Have a Dream" Speech". National Park Service. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- ^ Managing director: Joe Angio (2007-02-xv). Nixon a Presidency Revealed (idiot box). History Aqueduct.

- ^ "Vandals Deface Lincoln Memorial" Ocala Star-Banner (September 27, 1962)

- ^ Fard, Maggie Fazeli & Ruane, Michael E. (July 26, 2013). "Lincoln Memorial is shut downwards later vandals splash paint on it". The Washington Post . Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ Alexander, Keith 50. (January six, 2015) "Instance dismissed against woman accused of throwing dark-green paint on D.C. landmarks" The Washington Post

- ^ Staff (Feb 21, 2017) "Globe War II Memorial, Lincoln Memorial, Washington Monument, DC War Memorial Vandalized" NBC 4 Washington News

- ^ Staff (August 15, 2017) "Lincoln Memorial Vandalized With Red Spray Paint" NBC 4 Washington News

- ^ Reuters (Baronial xv, 2017) "Lincoln Memorial in Washington Defaced With Expletive" The New York Times

- ^ Mower, Justin Wm. (September 19, 2017). "Constabulary arrest man defendant of vandalizing the Lincoln Memorial with a penny". The Washington Post . Retrieved twenty September 2017.

- ^ LeBlanc, Paul (31 May 2020). "Famed DC monuments defaced afterward night of unrest". CNN . Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- ^ @NationalMallNPS (31 May 2020). "In the wake of last night's demonstrations, at that place are numerous instances of vandalism to sites around the National Mall. For generations, the Mall has been our nation's premier civic gathering infinite for non-violent demonstrations, and we ask individuals to carry on that tradition" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Rosales, Jean K. and Jose, Michael R. (2003) DC Goes to the Movies: A Unique Guide to Reel Washington iUniverse. p.149 ISBN 9780595267972

- ^ Reinhart, Marker S. (2009). Abraham Lincoln on Screen: Fictional and Documentary Portrayals on Film and Television. McFarland. ISBN978-0-7864-5261-3.

- ^ Toney, Veronica (September 17, 2015). "It's non just 'Forrest Gump.' The National Mall has had an iconic role in many movies". The Washington Postal service . Retrieved 12 Feb 2017.

- ^ Rosales, Jean K. and Jose, Michael R. (2003) DC Goes to the Movies: A Unique Guide to Reel Washington iUniverse. p.245 ISBN 9780595267972

- ^ a b Sacher, Jay (May 6, 2014). Lincoln Memorial: The Story and Design of an American Monument. Chronicle Books. pp. 83–85. ISBN9781452131986 . Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ "Permit FAQS" National Park Service

- ^ Mitchell Newton-Matza (2016). Historic Sites and Landmarks that Shaped America. ABC-CLIO. p. 324. ISBN9781610697507.

- ^ Tracey Golden Bennett (2014). Washington, D.C., Film and Telly. Arcadia. p. 27. ISBN9781439642764.

- ^ Bowers, Q. David (2008). A Guide Book of Lincoln Cents. Atlanta, Georgia: Whitman Publishing. pp. 45, 49–51. ISBN978-0-7948-2264-iv.

- ^ "$v". U.S. Currency Instruction Program. The states Regime. $five Notation (1914–1993) (PDF). Retrieved May 28, 2018.

Further reading [edit]

- Dupré, Judith (2007). Monuments: America's History in Fine art and Memory. Random Business firm. ISBN 978-1-4000-6582-0

- Hufbauer, Benjamin (2006) Presidential Temples: How Memorials and Libraries Shape Public Memory. Academy Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700614222.

- Pfanz, Donald C. (March iv, 1981). "National Annals of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination Form: Lincoln Memorial". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 24, 2012. Retrieved 2009-11-03 .

- Sandage, Scott A. (June 1993) "A Marble House Divided: The Lincoln Memorial, the Ceremonious Rights Movement, and the Politics of Memory, 1939–1963", Journal of American History Vol. fourscore, No. i, pp. 135–167

External links [edit]

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

- Lincoln Memorial homepage (NPS)

- Lincoln Memorial Panoramic Tour

- "Trust for the National Mall: Lincoln Memorial". Trust for the National Mall. Archived from the original on 2011-06-12.

- "Colorado Yule Marble – Building Stone of the Lincoln Memorial;" (PDF). US Geological Survey – Bulletin 2162; 1999.

- "Lincoln Memorial Drawings". National Park Service. 1993. Archived from the original on 2008-10-16.

- Other Proposed Designs for the Lincoln Memorial

- "American Icons: The Lincoln Memorial". Studio 360. Episode 1637. New York. September 10, 2015 [February nineteen, 2010]. Public Radio International. WNYC. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved September 13, 2015. How the Lincoln Memorial became an American icon.

dillinghamwherfust.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lincoln_Memorial

Postar um comentário for "Lincoln Memorial Site Plan Drawing"